How to Cut a Card by Lawrence Zhou

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Victory Briefs.

Lawrence Zhou was the 2014 NSDA National Champion in LD. He is an assistant coach at the Harker School and the Co-Director of Lincoln-Douglas Debate and Director of Publishing at Victory Briefs.

As we transition into the off-season and many tournaments around the country are being cancelled out of an abundance of caution due to fears of COVID-19, now is as good a time as any to start learning some new skills.

This article is going to cover how to cut a card in-depth. This is primarily aimed for more traditional circuits and younger debaters who may have reverse engineered how to cut a card, but never learned exactly how to do it. Of course, more experienced debaters can use this as a learning tool for their novices or to brush up their own card cutting skills.

What is a Card?

Back in the days before the Internet and using computers to debate in round, debaters would literally go to libraries and photocopy sections of books and articles onto little 5x7 notecards to use as evidence in round. That is where the name “card” is derived from.

Of course, today we don’t live in such ancient times and are now heavily reliant on the Internet for the vast majority of our debate research. But the purpose of a card has fundamentally remained the same.

A card is a piece of evidence or quoted material from authoritative sources, such as newspapers, journals, and credible blogs. The thing that makes a card different from evidence you might use for writing an English paper is mostly in the way that it is formatted. Card cutting refers to the process of collecting and formatting that evidence for use in competitive debate tournaments.

Cards are formatted differently by different people. What I will present here in this post is my personal process for cutting cards and my personal way to format cards. However, there should always be a few features that remain consistent across all types of cards, at least according to the Evidence Rules provided by the National Speech and Debate Association. I would encourage debaters (even the more experienced ones) to review the complete Evidence Rules as stipulated by the NSDA of their Unified Manual starting on page 29.

To summarize the manual, debate evidence must contain written source citations that include, at a minimum, the author name, publication date, source, title of article, date accessed, URL, author qualifications, and page number(s). Failure to adhere to these evidence standards can result in a loss or even a report to the tabroom (see the NSDA Debate Evidence Guide for reference).

Why Cut Cards?

Evidence in debate is primarily used to establish credibility. High school debaters are simply not qualified or knowledgeable enough to make assessments and predictions of the real world, especially when it concerns empirical claims. Evidence, then, is used to reference an authoritative source who is qualified to speak to on a certain subject area. For example, when making assessments about the likely economic impact of enacting a certain government policy, we should prefer to listen to the predictions of an economist over the musings of a high school student.

The problem is that evidence is usually very long. The longest speech in a debate is 7 minutes long which means that reading an entire article or news source as evidence to support a claim would occupy the entire 7 minutes, leaving the debater with no time to make other arguments. We want to hear evidence in debates, but there are time constraints that prevent debaters from reading too much evidence.

That's where the process of card-cutting comes in: it allows debaters to read evidence that has been shortened for the purpose of being read in a competitive debate with time limits.

Why don’t you want to paraphrase?

Many younger debaters and debaters in traditional circuits have a tendency to paraphrase evidence, where they might attribute an argument to a source but they won't quote directly. Not only does this run into problems with NSDA evidence rules, but it lacks the authority that comes with direct quotations. It's impossible for opponents or judges to verify if a paraphrase is accurate in the context of a debate round. Quoting from the source directly enables opponents and judges to see if you're accurately summarizing the argument being made which lends credibility to the argument.

Why not use ellipses?

Short answer: That violates NSDA evidence rules and you can lose rounds for doing this.

Tools for Card Cutting

The following are some tools I recommend for card cutting. The first 2, in particular, are almost necessities for efficient card cutting.

Verbatim

https://paperlessdebate.com/verbatim/

If you’ve never heard of Verbatim, this will fundamentally change how you do debate research. Verbatim is a series of macros designed for Microsoft Word that makes debate research, file organization, and in-round debating significantly easier.

If you do not have Microsoft Word, I strongly recommend you get it. Most high schools have a plan that allows you to download it for free or reduced price. If that’s not an option, it’s worth convincing your parents to pay for it. It’s one of the few pieces of software I willingly pay money for because it’s value to a debater is nearly immeasurable. Believe me, I’ve used Open Office, Google Docs, and the Mac’s vastly inferior Pages before – none of them stack up against the sheer versatility that Microsoft Word offers.

For this post, we’re going to ignore a lot of the features of Verbatim, including its usefulness as an organization and in-round tool. We’re just going to focus on how Verbatim can help you cut a card. Everything you need to know about Verbatim will be explained below in the article.

If you’d like to learn more about Verbatim, simply Google “Verbatim Tutorial” and you’ll find many tutorials on Youtube that will walk you through all the basic functions of Verbatim. If you have a Windows machine, there’s even a built-in tutorial when you first launch Verbatim and which you access by clicking “Settings”, “Verbatim Help”, and then selecting “Tutorial”.

For debaters without Microsoft Word, it is still possible to cut cards, but the process will be noticeably more time intensive. You can still follow along with the tutorial below but it will not be quite as easy.

As a sidenote, Verbatim is notoriously finicky with Macbooks, especially the newer versions of Microsoft Office. It’s most reliable with Word 2011 on Macbooks. (This is part of the reason why I sold my previous Macbook in favor of a Windows device.)

Cite Creator

Cite Creator is a Google Chrome Extension (available here) that produces academic citations for use in competitive debate. While other options for automatic citations exist (e.g. Citation Machine and Easybib), I've found that they are not as convenient to use for debate (although I do still use them when doing academic work for school).

After you install Cite Creator as an Extension, it will attempt to create citations for any web page you visit in a little black box in the corner of your browser.

The picture below shows the basic controls of how to use Cite Creator.

Here are the modifications I’ve made to my Cite Creator settings to make it work for me, which you can access by clicking the "Options" button.

If anyone would like to use the citation style that I use instead of the standard cite format, feel free to copy the custom settings that I use. This will be the citation format for the example card we'll cover below.

%author%, %y% -- %quals%[%author%, "%title%," %publication%, %date%, %url%, accessed %accessed%]

Of course, you can create your own citation style using the codes in the plug-in and many people have different citation styles they personally like. As long as the citation has the minimum required components by the NSDA, the exact format doesn't matter too much.

A Nice Mouse

Not all computer mice are created equal. In my opinion, a good mouse is incredibly helpful for card cutting because the process of formatting evidence requires precision and because mice with programmable buttons help take advantage of the macros in Verbatim.

At the bottom of this post, I’ll provide a list of my favorite recommended mice.

The Process of Cutting a Card

We’re going to go step by step through the process of cutting a card. I’ll show you each step I take for getting a news article into a debate ready-to-read piece of evidence using Verbatim.

1. Find the paragraph(s) you want to cut.

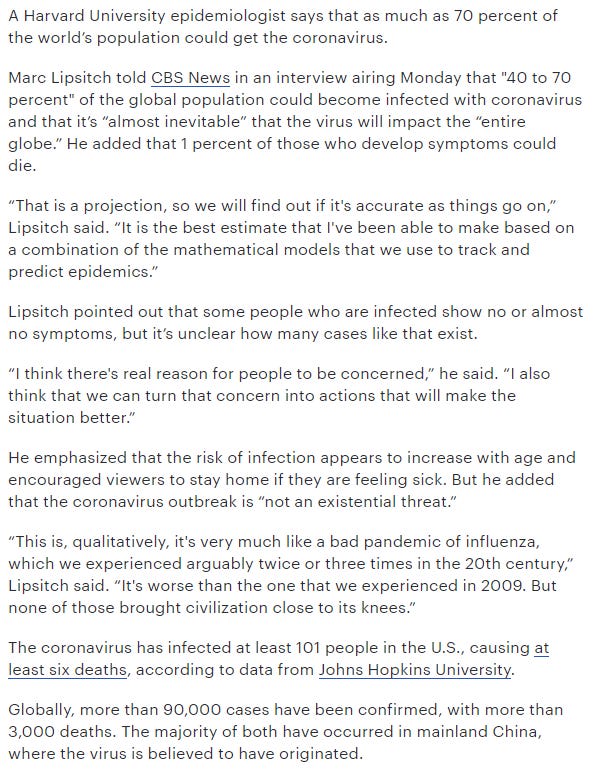

In light of the COVID-19 scare, I wanted to find a piece of evidence that was relevant to our current predicament. We’re going to use the article “Virus expert: As much as 70 percent of world's population could get coronavirus” from the Hill. Here is a screenshot of the short article:

We’ll be using this article as our example for cutting a card.

2. Copy and paste that text into Verbatim.

Select the text from the article and paste it into your open Verbatim document. Make sure that you are using the F2 button to paste text, so it eliminates the wonky formatting that many websites use.

You must include at the least full paragraphs you are cutting from. You may not copy and paste sections of a paragraph, where it starts in the middle of a paragraph, or the middle of a sentence. It is usually best to copy and paste more rather than less. For example, if you are copying the example article, it would not be okay to start at “It is the best estimate that I’ve been able to make…” You must start at “That is a projection, so we will…”

When it comes to a piece of evidence this short, I personally prefer to condense the evidence into a single block of text. To do this, select all of the paragraphs and click F3 or the “Condense” button in Verbatim. It should now create a single block of text that is much easier to read.

3. Add the citation.

Many younger debaters forget to add in the citation and I sometimes have a habit of forgetting. To ensure this doesn't happen, I always add in the citation before I go any further.

Remember, there is no 1 correct way to cite your sources, but you must cite them in compliance with the NSDA rules. The following is based on the citation created by Cite Creator using the format I created myself.

This citation is lifted almost directly from the Cite Creator Chrome Extension referenced above. To copy the citation from Cite Creator, simply click Ctrl+Alt+C on the web page where the evidence was accessed from and then paste it (using the F2 button) in the document right above the text of the evidence.

However, Cite Creator doesn’t always get it right (for example, on New York Times Op-Ed pieces, it almost always calls the title of the piece “Opinion”, instead of the actual Op-Ed article title). While most of the information in this citation was correct, sometimes you’ll have to manually add in or fix some of the citation information. Here, I had to manually add the author qualifications by searching the author’s name on the Internet and fix the spacing issue between “The” and “Hill” in the source of publication section. It is your responsibility to ensure the citation information is correct.

Notice in this example that the author’s last name and the year of publication are in bold and out in front of the rest of the citation. That is because in a speech, you must read (at least) the author’s last name and year it was published.

4. Underline the evidence.

Next, we're going to begin shortening the evidence. The process of shortening evidence occurs in 2 steps: underlining and highlighting. We're going to start with underlining.

When underlining evidence, you should be focused on getting rid of extraneous words, phrases, and sentences that don't meaningfully contribute to the central idea of the article or the argument you want the evidence to make.

To underline your card:

Read through the evidence.

Select any text that you think might be important.

Click the F9 (underline) button.

Continue until finished with the card.

There is no one correct way to underline evidence (and indeed, the underlining may change depending on what the intended purpose of the evidence is). The following is how I underlined the article:

Notice in my example, I underlined more than half of the evidence. This is a personal preference. You can choose to underline more or less. I personally choose to underline more because on this first pass through, I'm mostly focused on getting ridding of the parts of the evidence that I don't think are that important. For example, I didn't underline any parts that include phrases like "he said," "he added," or "he emphasized" because those are all unnecessary words. I also eliminated a few sentences that don't overall add to the argument the evidence is trying to make. I will eventually make the evidence much shorter in the next step.

However you want to underline your evidence is up to you. Each person will do it differently because these are basically different interpretations of the same piece of evidence. As long as you're focused on selecting the important information, then you're on the right track.

Optional: Add “Emphasis” to the evidence.

The following step is completely optional, but you can add emphasis to your evidence. Most debaters add emphasis for rhetorical or aesthetic purposes. Emphasis aids in rhetoric because those are important phrases that you might want to verbally emphasize when you're reading evidence aloud in a speech. Some simply add in emphasis for aesthetic purposes because they enjoy the way that evidence with emphasis looks in their document (weird, I know).

To add emphasis to your card:

Read through the evidence again, this time only reading parts that you've underlined.

When you come across words or phrases that seem important, select it.

Add the "Emphasis" style by clicking the F10 button.

Continue until finished with the card.

Your card should now look something like this:

Here, I added emphasis to words and phrases I thought had some important punch to them. For example, I personally liked the phrases "impact the 'entire globe'," "'not an existential threat'," and "'none of those brought civilization close to its knees'" because they helped convey the central point of this article using clear language. You might have picked different phrases or words to emphasize; that's totally fine. Just make sure you understand why you're picking those words or phrases.

Again, this step is totally optional but I do strongly recommend it because it forces you to read through your evidence one more time before you move on to the last step.

5. Add highlighting.

We're almost done! The next step is the most important: highlighting. With underlining, we were mostly just trying to get rid of the unimportant parts of the evidence. With highlighting, we're just trying to get the evidence into the shortest possible version while not compromising on the warrants because only the highlighted portion will be read in a debate round.

To highlight your card:

Select the Highlighter tool.

Select the text that you think is important for making your argument.

Continue until finished with the card.

Your card should now look something like this:

Remember, we only read the highlighted portion in a debate round. So, instead of reading "A Harvard University epidemiologist says that as much as 70 percent of the world’s population could get the coronavirus" we now say "A Harvard epidemiologist says 70 percent of the world could get coronavirus." Both sentences are (more or less) grammatically correct, but the second one is much shorter while still conveying the same information.

You'll also notice that I highlighted parts of words, e.g. "influenza" was highlighted as "flu." This is acceptable if, and only if, you are not changing the original argument made by the author.

It will take time to figure out what is important to highlight and what isn't, especially since that might change depending on the context. Work with your coach, teammates, or friends and ask them to review what you've highlighted. They may have tips or suggestions for improving the highlighting of your card.

6. Add a tagline.

Last step is the easiest. Now we just need a tagline. A tagline is an introduction to the evidence written by the debater.

At this point in time, I have read through this paragraph 3-4 times so I have a good understanding of the evidence. I know that it is saying 3 main things: the spread of coronavirus is likely inevitably going to impact the vast majority of the planet based on expert models, that this impact is reason for some serious concern, and that the pandemic will not rise to the level of an existential threat based on previous pandemic threats.

I personally don't think the second main idea is that relevant, so I'm going to focus on the first and third. I want a tagline that quickly summarizes those ideas in a way easily understandable by many judges. I personally prefer shorter taglines since you can always explain your evidence in subsequent speeches and longer taglines rarely help.

Here, I'm just going to summarize the evidence as "Coronavirus is inevitable but not existential." But any tagline that tries to convey something similar would also be acceptable. Again, there is no one right answer here; just pick one that you like and you can always change it later.

To add the tagline to your card:

Place your cursor above the citation.

Write the tagline.

Apply the "Tag" style to the sentence(s) you just wrote by clicking the F7 button.

Your card should now look something like this:

Optional: Shrink the text.

You can go the extra step and shrink all the words that are not underlined into a smaller font. Many debaters prefer to do this to shorten the amount of space a card takes in a document, to increase readability, or for aesthetic purposes. Whether or not you shrink the un-underlined text is a personal choice.

To shrink the text:

Select the paragraph you'd like to shrink.

Click the "Shrink" button in the Format menu.

The card should now look like this:

Congratulations, you’ve finished cutting a card!

However, I personally hate the way that the default formatting looks in Verbatim and I especially despise Calibri (eww), so this is how that same card would look using my personal formatting preferences:

If you’d like to emulate my formatting practices, these are the settings that I personally use:

You can find these under “Verbatim Settings” and the “Format” tab. I would also recommend playing around with these until you find something that you or your team likes.

Recap

To recap, a card is composed of 3 parts: a tagline, citation, and body of evidence.

Tagline: A tagline introduces the main idea of the card. Taglines can be short or long, as long as they accurately summarize or represent the evidence.

Citation: The citation has 2 parts: the verbal and written citation. The verbal citation includes, at a minimum, the last name of the author and the year of publication, although debaters may choose to add additional information like qualifications if desired. This is what is read aloud in a competitive debate round and is read before the rest of the evidence. The written citation complies with the NSDA Evidence Guide and contains all other relevant publication information that must be easily accessible during a debate round.

Body of Evidence: The body of evidence contains the original piece of evidence in its full form with modifications. A card usually contains underlining and highlighting designed to maximize efficiency. In a debate round, only the parts that are highlighted are read aloud. The rest of the text is kept so that it is easily accessible during a debate round.

Only the tagline, verbal citation, and highlighted parts of the evidence are read aloud in a debate round. The rest of the information simply needs to be written down in order to comply with NSDA rules.

In case this was difficult to follow on with, there is a Word document attached at the bottom of this post that you can download to see the stages of cutting a card. You can manipulate the document to see how card cutting works.

Miscellaneous Questions

1. Should there be “paragraph integrity”?

This is a somewhat controversial question. Paragraph integrity refers to maintaining the distinctions between the various paragraphs in an article. Using the article referenced above, you can see that there are 9 distinct paragraphs. However, in the card that we cut, we collapsed all the paragraphs into a single block of text for ease of reading. There is no hard and fast rule for questions of paragraph integrity. Many younger debaters tend not to maintain it, at least partially due to the fact that when you select the “Condense” option in Verbatim, it automatically collapses all the paragraphs into a single block of text. To change this, simply go to Verbatim Settings, select the “Format” tab, and select “Retain Paragraphs” under the “Condense” box. When this is selected, the selected text will keep the distinction between different paragraphs.

More advanced debaters tend to keep paragraph integrity, especially when they cut evidence from more advanced sources like law journals. There are a few reasons for this preference. Some prefer to keep it simply for aesthetic purposes, as large blocks of text tend to be difficult to read and look unorganized. Some keep paragraph integrity because they tend to cut very long cards (where a single piece of evidence might be selected from multiple pages) and the paragraph integrity is critical to keeping it readable. Others may keep paragraph integrity because they may want to modify the evidence by shortening it and maintaining paragraph integrity allows them to find a clear spot to end the evidence. Whatever the reason, this is mostly a personal preference. Personally, I keep paragraph integrity on longer pieces of evidence where each paragraph is quite lengthy but prefer to collapse the evidence into a single block of text for shorter pieces of evidence from news sources.

2. Can you use footnotes/endnotes?

You can; however, it is not common practice anymore. Debaters used to heavily employ footnotes or endnotes in their citations. Nowadays, it looks a little silly, makes it more difficult to reference relevant information about your sources in cross-examination or during a speech, and simply adds more unnecessary work. In general, it is best to simply stick with the style of card-cutting presented here (or something similar) with a tagline, citation, and evidence.

3. How do I improve at card cutting?

There is no substitute for practice. Card cutting involves taking advanced arguments and knowledge and distilling it down to a short and understandable form. This is a challenging prospect and there is no shortcut for improving. Read more and cut more cards. This is the way.

When you have free time, you should strive to cut cards as practice. Especially now, when there is a lot of free time, use it to practice building a file. Think about a generic subject that applies to a lot of different topics (e.g. debates between utilitarianism and deontological ethics or economics questions about the goodness and badness of the free market) and try and cut cards about those subjects. Strive to cut a few a day. The more you cut cards, the better at it you'll become. You'll soon learn what's important to include and what's not. You'll see clever ways to make your cards shorter without compromising on the depth of warrants in the evidence. This will all come in due time, but you have to commit to practicing.

Mouse Recommendations

The computer mice I recommend are wireless (they are simply more convenient to store in a backpack while traveling) and have programmable buttons. The programmable buttons are what's important: they allow you to assign them to macro keys. For example, I have one button on my Logitech MX Anywhere 2S assigned to the F9 button in Word which allows me to underline and the second button assigned to the F10 button in Word which allows me to add emphasis. This way, when I'm cutting a card, I don't need to use the keyboard. I can simply select text, click the button on my mouse, and the text will be automatically underlined.

Mice that I have used and can personally recommend because of how comfortable they are and how effective they are for debate are:

The Logitech MX Master 3: The recommended mouse by many Tech Youtubers, it’s pricey but an investment. It’s precise, comfortable, and has several buttons that can be used with Logitech Options software to help cut debate evidence. The previous models are cheaper although I personally did not like the feeling of the MX Master 2.

The Logitech MX Anywhere 2S: This is my preferred travel mouse due to its compact size and great form factor. It can use the same Logitech Options software to reprogram its two side buttons for card cutting. It's so good that when I lost one, I immediately replaced it the following day because I can't travel without it.

The Logitech G502: If you’re a gamer, you’ve surely heard about this mouse. I have the wired version, but when the wireless version goes on sale, this is a great deal and incredibly powerful for cutting cards.

I’ve also heard great things about the Razer Naga and various other gaming mice, although I’ve not been able to personally use them for extended periods of time, so I can't personally recommend them. Either way, do your research before you invest in such technology. The up-front cost is a lot, so you want the device to last you for years.

Here is a Word doc attachment where you can see each step of cutting a card in order: